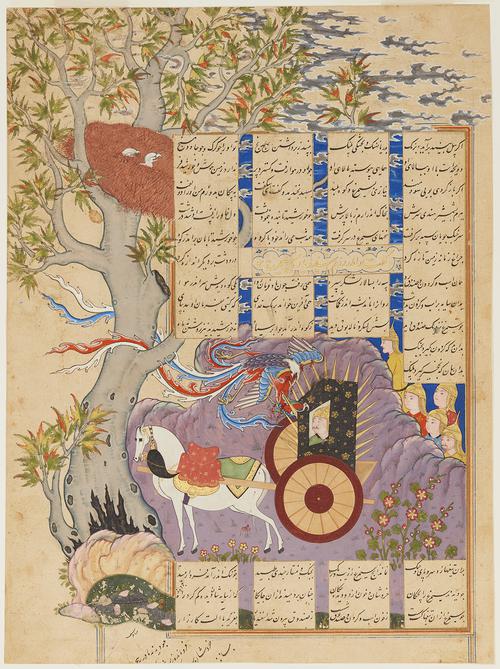

Click on the image to zoom

Isfandiyar kills the Simurgh

Folio from the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Ismail II

- Accession Number:AKM103

- Creator:attributed to Siyavusah

- Place:Iran, Qazvin

- Dimensions:40.4 x 29.8 cm

- Date:1576–77

- Materials and Technique:opaque watercolour, gold, silver and ink on paper

The miniature painting “Isfandiyar kills the Simurgh” is from a dispersed illustrated manuscript of the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), completed by the Persian poet Firdausi ca. 1010. Shah Ismail II (r. 1576–77) [1] commissioned the manuscript, following the examples of his grandfather, Ismail I, and father Shah Tahmasp, both of whom showed interest in Firdausi’s epic at one time during their reigns. Ismail II’s Shahnameh can be seen as a link in the chain of royal copies of the Book of Kings, after Shah Tahmasp’s spectacular manuscript and forming a bridge to the next period of royal patronage of the epic under Shah ‘Abbas (1587–1629). The manuscript was left unfinished upon Ismail II’s death. However, for a brief period, Ismail II’s atelier employed a number of artists who contributed to the illustration of the Shahnameh, including Siyavush, Sadiqi Beg, Naqdi, Murad Dailami and Mihrab. These artists did not sign their work, and attributions were probably made by the contemporary royal librarian. In its bottom left-hand corner, this painting is attributed to Siyavush.

See AKM70 for an introduction to the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Ismail II.

Further Reading

A Georgian slave at the court of Tahmasp, Siyavush was the main contributor to the illustration of this manuscript, completing an impressive total of 22 paintings. This painting concerns the fifth of the seven “labours” (Haft Khwan) of Prince Isfandiyar, son of Shah Gushtasp. Shah Gushtasp sent Isfandiyar to rescue his sisters from the Bronze Fort of Arjasp, with the false promise of the crown should he succeed. Isfandiyar’s fifth trial is an encounter with a phoenix-like bird called the Simurgh, which plays an ambiguous role in the Shahnameh: it is both the benevolent protector of the hero Rustam and saviour of his father Zal, and an evil, dragon-like creature who must be defeated by Isfandiyar.

In many respects, Isfandiyar’s seven trials match those of Rustam earlier in the Shahnameh (see AKM100). Their major differences involve methods of fighting.[2] Whereas Rustam fights adversaries (including a dragon) with his sword alone, Isfandiyar has a tank-like contraption in which he defeats first the dragon and then the Simurgh, who attacks and impales itself on the vicious blades attached to it.

This painting accurately reflects this moment, with the static horse and rather impassive hero sitting safely in his chariot while the colourful bird immolates itself on the spikes. As noted by Anthony Welch, “this is a powerful nature painting, intense in feeling and completely dominating the insignificant and unconcerned human beings below the tree.”[3] The magnificent tree and the dark, cloudy skies are carried on behind and through the lines of text above the rocky outcrop, a gesture towards the vast mountainscape where the Simurgh lived. Indeed, the painting does not depict this mountainous home as vast as Firdausi describes it (“blocking out the light of the sun and moon”). Neither are the two pathetic, frightened chicks in the nest above as fearsome as Firdausi indicates after the death of their mother. In Firdausi’s verse, they fly away, supposedly “so large that their shadow blinds the sight.” Here, however, the artist manages to enlist the viewer’s sympathy for the bird and its chicks rather than celebrate the heroism of the champion.

It is interesting to compare this painting with another in Shah Ismail II’s Shahnameh, namely “Sam visiting the Simurgh in the Alborz Mountains,” attributed to Sadiqi Beg. Sam hopes to reclaim his son Zal, whom the dramatically plumed bird returns in its claws.4 The tone and colours in Sadiqi Beg’s painting strike a more optimistic note, and the balance between the human and supernatural elements is more even.

The page has been trimmed and pasted onto card, evidence of the unscrupulous activities of Belgian art dealer Georges-Joseph Demotte (d. 1923). Shortly after a 1912 exhibition at the Musée des arts décoratifs in Paris, Demotte dismembered Shah Ismail II’s copy of the Shahnameh. He then sold its pages to a number of collectors, including the Baron Edmond de Rothschild.

The Aga Khan Museum Collection has eight folios from the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Ismail II, see AKM70, AKM71, AKM72, AKM99, AKM100, AKM101, AKM102, AKM103.

— Charles Melville

Notes

[1] Shah Ismail II was the third ruler of the Safavid dynasty (1501–1722). Reuniting the eastern and western provinces of Iran, the Safavids introduced Shiite Islam as the official state religion. Ismail II, son of Tahmasp (r. 1524–76), seems to have been inclined to return to Sunnism, but in this and his artistic patronage he was perhaps simply seeking to distance himself from his father’s regime. He was murdered after ruling for 18 months.

[2] Davidson, Poet and Hero, 162-63.

[3] See Welch, Artists for the Shah, 24-25, fig 2. See also the full colour reproduction and translation of part of the text by Assadullah Souren Melikian-Chirvani, Le chant du monde. L’Art de l’Iran safavide 1501-1736, Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2007, 278-279, no. 71.

[4] Reproduced in Melikian-Chirvani, 284–85, no. 74; see also Robinson, “Isma‘il II’s copy of the Shahnama,” 3, pl. Iva.

References

Davidson, Olga M. Poet and Hero in the Persian Book of Kings. Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1994. ISBN:9780674073210

Melikian-Chirvani, Assadullah Souren. Le chant du monde. L’Art de l’Iran safavide 1501–1736 Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2007. ISBN: 9782757201268.

Robinson, BW. “Shah Ismā‘īl II’s copy of the Shāh-nāma: Additional material,” Iran 43 (2005), 291-99. DOI: 10.1080/05786967.2005.11834675

Welch, Anthony. Artists for the Shah. Late Sixteenth-Century Painting at the Imperial Court of Iran. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1976. ISBN: 9780300019155.

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.