Click on the image to zoom

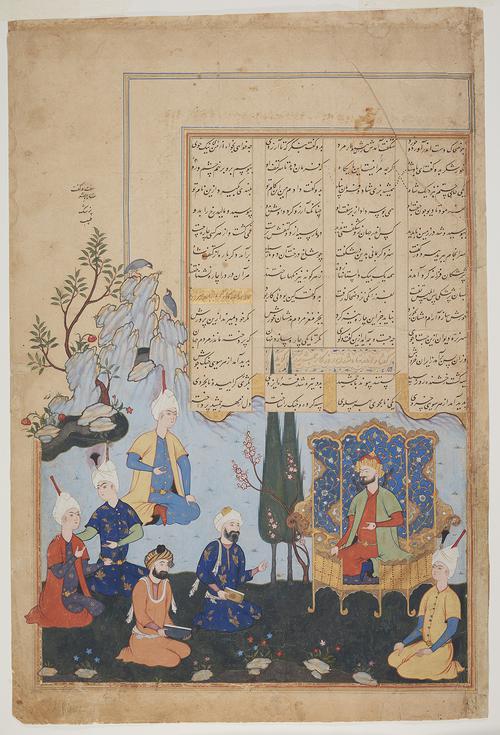

Zahhak Consults the Physicians, Folio from the Book of Kings (Shahnameh) of Shah Ismail II

- Accession Number:AKM71

- Creator:Artist (painter attributed): Naqdi Author: Firdausi, Persian, ca. 935 - 1020 Created for: Shah Isma`il II, 1537 - 1577; r. 1576-1577

- Place:Iran, Qazvin

- Dimensions:45.7 cm × 30.7 cm

- Date:ca. 1576

- Materials and Technique:Opaque watercolour, gold, silver and ink on paper

The miniature painting “Zahhak consults the physicians” is from a dispersed illustrated manuscript of the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), completed by the Persian poet Firdausi ca. 1010. Shah Ismail II (r. 1576–77)[1] commissioned the manuscript, following the examples of his grandfather, Ismail I, and father Shah Tahmasp, both of whom showed interest in Firdausi’s epic at one time during their reigns. Ismail II’s Shahnameh can be seen as a link in the chain of royal copies of the Book of Kings, after Shah Tahmasp’s spectacular manuscript and forming a bridge to the next period of royal patronage of the epic under Shah ‘Abbas (1587–1629). The manuscript was left unfinished upon Ismail II’s death. However, for a brief period, Ismail II’s atelier employed a number of artists who contributed to the illustration of the Shahnameh, including Siyavush, Sadiqi Beg, Naqdi, Murad Dailami and Mihrab. These artists did not sign their work, and attributions were probably made by the contemporary royal librarian. This miniature is attributed to Naqdi in the left-hand margin, at the base of the tree. Six other paintings in this copy of the Shahnameh also bear Naqdi’s name.[2]

Further Reading

The text concerns the tyrant Zahhak, who was introduced to the delights of haute cuisine by Iblis. Zahhak rewarded Iblis by granting him permission to kiss his shoulders. Immediately, two black snakes appeared and grew again when cut off. Zahhak’s doctors could find no remedy, and Iblis reappeared in the guise of a physician to inform him that feeding the snakes with men’s brains would be the only way to keep the snakes satisfied. This scene is not often depicted, but a precedent in a manuscript dated 1518 in the John Rylands University Library, has a similar composition.[3]

The text above the painting is also noteworthy in two respects. In the third and fourth rows, the first half verse does not match the second: they are correctly paired up by the dotted lines in the first column. Two verses here are omitted altogether: “My (Iblis’s) heart is full of love for you entirely, my soul’s only sustenance is from (seeing) your face”; and “When Zahhak heard his (Iblis’s) words, he did not understand what he secretly wanted.”[4] In the margin on the top left of the page is written soft va ketf shaneh bashad (soft and ketf both mean “shoulder”) and pezeskh = tabib (“doctor” “nurse” in Persian and Arabic). In other words, these terms provide a glossary on words supposedly obscure in the text. The half verse at the end of line 8 has been gilded over to hide a mistake, though the correction does not follow the standard text.

The unusual layout of the page is characteristic of Ismail II’s Shahnameh. Common features include the double ruled margins (see also AKM70, AKM99, AKM101, and AKM102), the freedom with which the artist extends the painting beyond the frames, and the interactions between the picture and the text. Here, the gold sky is seen in the columns behind the last few verses above the picture, and the cypress trees penetrate into the box where the heading advertises the next scene, “Which tells of the ruin of Jamshid’s fortune (or fate).” The artist gives charming touches to the landscape, notably the birds.

Although Ismail II’s Shahnameh cannot compare with the magnificence of Shah Tahmasp’s copy, it is a large and impressive manuscript, important in its historical context and as a witness to the various talents and styles of a number of artists identified by name, who worked in the transitional period from the 16th to the 17th century and experienced the shift in focus from Qazvin to the new capital, Isfahan.

- Charles Melville

Notes

1. Shah Ismail II was the third ruler of the Safavid dynasty (1501–1722). Reuniting the eastern and western provinces of Iran, the Safavids introduced Shiite Islam as the official state religion. Ismail II, son of Tahmasp (r. 1524–76), seems to have been inclined to return to Sunnism, but in this and his artistic patronage he was perhaps simply seeking to distance himself from his father’s regime. He was murdered after ruling for 18 months.

2. See B.W. Robinson, “Isma‘il II’s copy of the Shahnama,” Iran 14 (1976), 1–8, and Robinson, “Shah Isma‘il II’s copy of the Shah-nama: Additional material,” Iran 43 (2005), 291–99. Anthony Welch, Artists for the Shah. Late Sixteenth-century Painting at the Imperial Court of Iran (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1976), 206–7 (for Naqdi). Sheila R. Canby, Princes, Poets & Paladins. Islamic and Indian Paintings from the Collection of Prince and Princess Sadruddin Aga Khan (London: British Museum, 1998), 57–58 and pl. 32. Robinson and Canby incorrectly refer to the painting as “Jamshid enthroned” and “The rule of Jamshid” respectively.

3. MS. Pers. 910, f. 23r.

4. Shahnameh, ed. by Jules Mohl, “Jamshid,” verses 170, 173; and ed. by Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh, “Jamshid,” verses 149, 152.

References

Canby, Sheila R. Princes, Poets & Paladins. Islamic and Indian Paintings from the Collection of Prince and Princess Sadruddin Aga Khan. London: British Museum, 1998. ISBN: 9780714114835

Khaleghi-Motlagh, Djalal, ed. Shahnameh. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers in association with Bibliotheca Persica, 1992

Mohl, Jules, ed. Shahnameh (Livre des rois). Paris: Impr. Nationale, 1876–78

Robinson, BW. “Isma‘il II’s copy of the Shahnama,” Iran 14 (1976), 1–8; reprinted in BW Robinson, Studies in Persian Art, vol. II (London: Pindar Press, 1993), 290–305. ISBN: 9780907132431

---. “Shah Ismā‘īl II’s copy of the Shāh-nāma: Additional material,” Iran 43 (2005), 291–99. DOI:10.1080/05786967.2005.11834675

Welch, Anthony. “Painting and Patronage under Shah ‘Abbās,” Iranian Studies 7, nos. 3–4 (1976), 458–508

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.